Sjekklister redder liv

Sist oppdatert:Snarveien: Det finnes to typer feil: De vi gjør fordi vi ikke vet hva som er riktig. Og de hvor vi glemmer å gjøre det. Sjekklister hjelper deg å huske de kritiske stegene.

Innlegget under er fra et foredrag jeg holdt på Haydom-sykehuset i Tanzania i 2013.

Etter det har jeg både brukt sjekklister under forbedringsarbeidet i AniCura og sett det i aksjon på operasjonsstuen på Ullevål.

På sykehuset var jeg imponert over disiplinen operasjonsteamet viste. Selv om de hadde jobbet sammen flere ganger før, gikk de slavisk gjennom alle punktene – inkludert presentasjonsrunden. Det var tillitsvekkende.

The Checklist Manifesto

In 1935 US Army Air Corps commissioned new bomber plane. Boeing’s proposal could carry 5 times as many bombs and fly twice as far as the closest competitor. Even though this was still formally a competitive bid, the Army had already ordered 65 planes from Boeing, making the following demonstration more of a formality than a sales pitch.

The army top officers came to see the test flight, flown by Major Pete Ployer Hill – the most experienced test pilot of his day. They watched the plane taxi along the runway, fly up to three hundred feet, before it stalled on one wing and crashed in a fiery explosion, killing two crew members, including Major Hill.

The investigation afterwards concluded that this was a pilot error. The plane was vastly more complicated than any plane before it, and the pilot had to maintain the fuel mix in each of the four engines, check the rudders, retract the landing gear, the hydraulic controls at the same time as flying. It was said that this was too much of an aeroplane for one man to fly.

This story is retold by the American surgeon Atul Gawande in his book The Checklist Manifesto. I’m neither a pilot nor a doctor, but I hope to convey to you some of the ideas on safety from Gawande’s book today.

Common mistakes lead to injuries

Why does Gawande tell this story? In 2008 he was asked to lead a conference on how to make surgery safer. Every year around 7 million people are disabled and 1 million people die from complications or mistakes in surgery, many of these being avoidable. Even reducing this number a little can save thousands of lives every year.

First Gawande and his team looked into why are these things happening? In other words, where do mistakes come from?

He posits that there are two types of mistakes:

- Mistakes from what we don’t know

- Mistakes from what we forget.

The more things we have to remember to do, the more things we will forget. Each patient in an intensive care unit has on average 178 actions performed him per day. An action in this sense is a step that the medical staff need to get right, broken into components. Giving an injection might consist of 12 action-steps, and so on.

If we make a mistake in 1 % of the actions, that means 2 errors every day per patient. Suddenly it is not so surprising to explain why up to 25% of patients get complications following treatment. Even on our best behaviour, we will all forget to do the right thing in a few cases. But the numbers add up, so how can we trust less in our fallible memories?

Gawande’s team looked into which other situations are extremely challenging and require vast knowledge to master. The key lay in the aftermath of the 1935 crash.

Introducing the checklist

Let’s go back to the Boeing 299. The plane was scrapped. If the Air Force’s most experienced pilot couldn’t even handle it, who could? It was just too complicated to fly.

The Boeing lost the contract. Nonetheless, the company continued working not only on the plane itself, but also the pilot’s ability to fly it. Note, however, that they did not do what others would have done:

- No extra training

- No more people in the cockpit.

Instead someone wrote checklists – for the first time in aviation history. The plane eventually took to the skies again, becoming the B-17 Flying Fortress, one of WWII’s most successful bombers.

There is just too much for a pilot to remember. A checklist takes some of the reminders from your head and puts them onto paper.

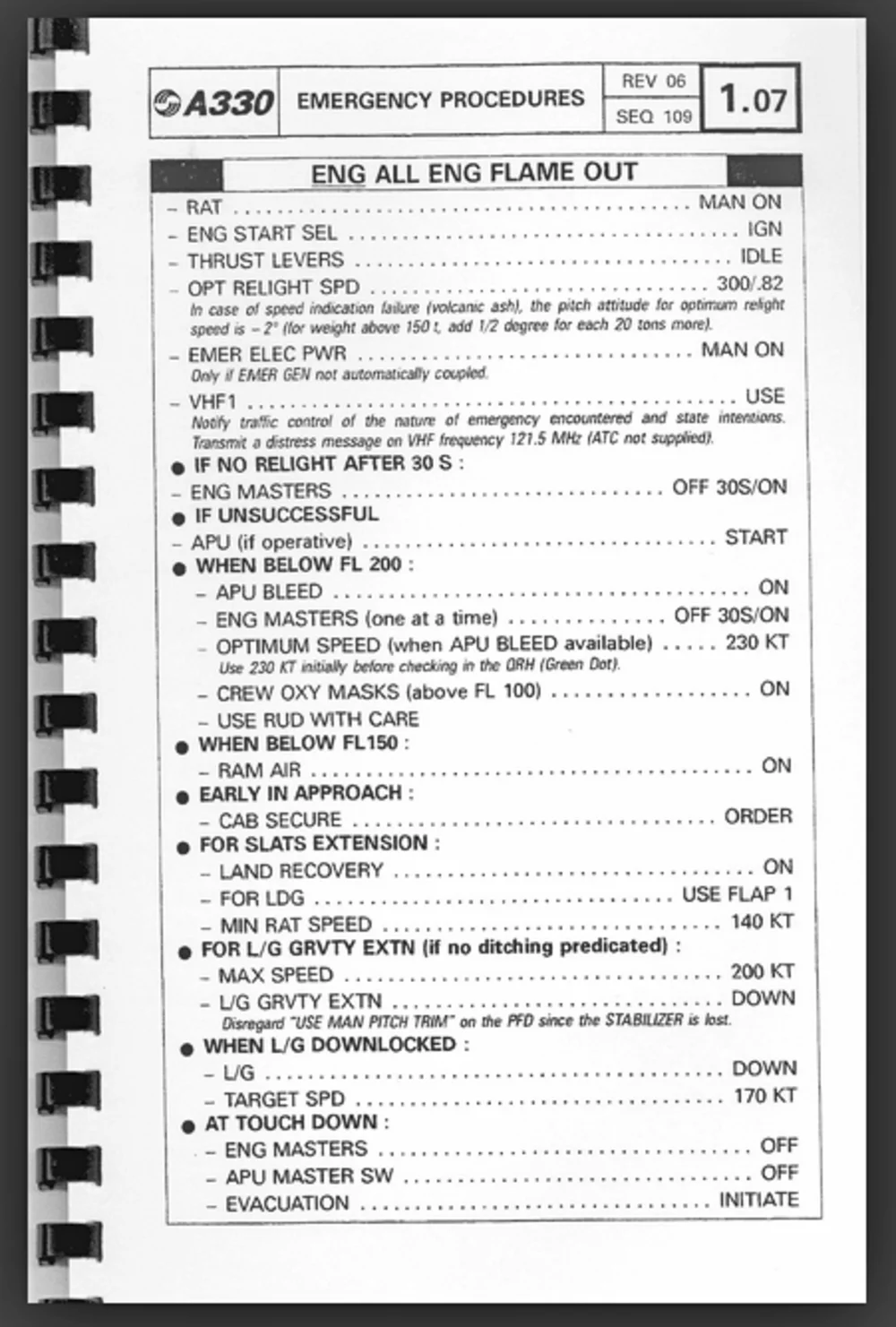

There are two types of aviation checklist: Standard and emergency. The standards take care of regular activities, such as take-off and landing.

The emergency lists are an easy-to-look-up library of common failures. When Captain Sully landed on the Hudson river, he and his co-pilot used both and engine failure- and quick ditch checklist.

Notice how simple the aviation list above is – containing only the critical steps.

A common critiscm of checklists is that remove the thinking and skill from the pilot. But take a look at the lists. They only contain the critical steps – cutting through the chaos of too many options to consider. The checklist helps the pilot remember which common sense options are open to him, not to take away his judgement.

Gawandes team made a trial of 8 hospitals around the world, one even here in Ifakara, Tanzania. They monitored complication rates before and after. At no extra costs the hospitals reduced the rate of complications by 36 % and the risk of death by 47 %. To have something to compare that to – a hospital the size of Haydom has maybe 3500-4000 operations a year. If we have complication rates similar to other hospitals that means that a 30% reduction leads to 150 patients each year who do not have to stay and pay more than they have to, and 50 lives being saved.

Lessons from checklists

So what did he learn from the people who make checklists?

They have to be short. If they take more than 90 seconds to run through, they are too long.

Focus on the killer items, the critical things that are easy or dangerous to miss.

They have to be practical to the people who use them.

They have to have a clear pause point for when to use the list. “If this situation, then use that list”.

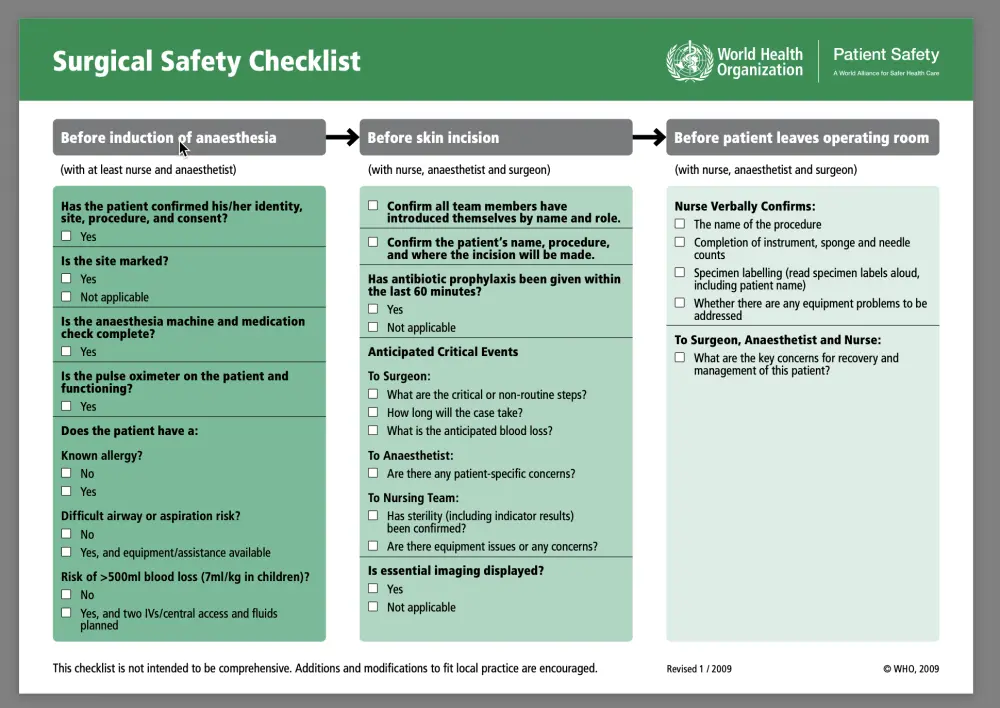

WHO’s list

Here’s the list the WHO recommended. Many of you have already seen it, but I think it can be particularly interesting to those of us that are not medical.

Notice how simple it is. See the pause points.

This is an example of a Do-Confirm list. Everyone does their job, and then you stop and confirm that you’ve done it. The alternative is a Read-Do list, like a recipe.

I will not go through it, as the details can be read on the WHO page, and here is a booklet. But notice what is says on the bottom: Additions or modifications are encouraged. They want people to adapt to their surroundings! On the page there are many examples of checklists from other places.

I know for every complicated situation I will be in I am bound to make avoidable mistakes. And knowing that some of the best surgeons, pilots and engineers in the world use check lists inspires me to do the same.

Gawande sums it up: Using a check list does not dumb you down. Instead, it frees the brain to rise above the routine stuff and concentrate on the hard stuff. Good luck.